![]()

![]() exploring Bremen & its surrounding areas

exploring Bremen & its surrounding areas

![]() You are here: backgroundstories

You are here: backgroundstories

Gesche Margarethe Gottfried: The Bremen Poisoner

Gesche Margarethe Gottfried: The Bremen Poisoner

The black American comedy Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), featuring Cary Grant in one of the lead roles, could have at least partially served as inspiration for a sensational murder spree in Bremen - but it came about 130 years too late.

At the center of this criminal case in the early 19th century was Gesche Margarethe Timm, born in 1785 under rather modest circumstances and later known as Gesche Gottfried. In 1806, she ascended socially through her marriage to the saddler master Johann Miltenberg, becoming part of Bremen’s respectable bourgeois population. However, the arranged marriage - not founded on love - was unhappy. Miltenberg drank excessively, frequented taverns and brothels, and died on October 1, 1813, after squandering his family’s fortune.

Two years later, between May 2 and September 22, her two surviving parents and three children (two daughters and a son, aged three to six) died suddenly. Since she always presented herself as a caring wife, mother, and daughter to the public, the sympathy of her fellow citizens outweighed suspicion, earning her the nickname "Angel of Bremen."

The former detention house, now the Wilhelm Wagenfeld House at Ostertor, served as a Gestapo prison between 1933 and 1945

A year later, death struck her family again. This time, it was her long-lost twin brother, who reappeared as a nearly penniless and gravely ill soldier, demanding the inheritance due to him after their parents' deaths. Since she lived extravagantly and often struggled with debts - though this remained largely hidden from the public, who still believed her wealthy - the demand put her in a precarious situation. A generous portion of shellfish she cooked for him ended his life abruptly on June 1, 1816, thanks to the arsenic she had concealed in it.

Her longtime lover and friend of her late husband, the wine merchant Michael Christoph Gottfried, was increasingly unsettled by the numerous deaths in her immediate family circle. Thus, he hesitated to marry her despite her pregnancy. He did not live to see the stillbirth of their child, for she administered portions of her remaining arsenic supply, which slowly wasted him away until he died on July 5, 1817 - though not before marrying her out of gratitude on his deathbed and making her his heir.

Within just four years, seven people had died by her hand through arsenic poisoning without arousing judicial suspicion. However, this was not the end. After her second husband’s death, it seemed as though the tragic series of deaths in Gesche Gottfried’s family had ended - until several years passed with no incidents. The explanation was rather mundane: she had run out of poison. Ironically, she had received the "Mäusebutter" (a mixture of arsenic and lard for pest control) from her mother years earlier, who had been poisoned with it herself.

Her maid and friend Beta Schmidt eventually procured more "Mäusebutter" in 1823 after seeing an advertisement in a newspaper. Soon afterward, on June 1, 1823, Gesche Gottfried’s new fiancé, the fashion merchant Paul Thomas Zimmermann, fell victim to poisoned spread on zwieback and died after prolonged agony. Once again, she inherited a small sum. Afterward, she began administering smaller, non-lethal doses of poison to people around her. It was not until two years later that Gesche Gottfried gave another fatal dose - this time to her longtime friend, the music teacher Anna Lucia Meyerholz. By the end of the same year, a neighbor with whom she also shared a long friendship succumbed after prolonged suffering.

Her extravagant lifestyle eventually forced her to sell her residence on Pelzerstraße, though she retained the right to live there. Thus, she soon moved back into the house with its new owners - the wheelwright couple Wilhelmine and Johann Christoph Rumpff - and their employees, managing the household. Wilhelmine Rumpff died shortly after giving birth on December 22, 1826, after Gesche had administered "Mäusebutter" to her twice. Following numerous non-lethal poisonings, she finally killed her longtime friend Beta Schmidt and the woman’s three-year-old daughter with poison in May 1827 - the mother surviving her child by only two days.

Her final victim was an old business associate in Hanover, the locksmith Friedrich Kleine. She owed him money that he demanded but which she could not repay. About two months after her double murder, she sent him to the grave as well and told his relatives that she had paid her debts, even offering them small portions of "Mäusebutter."

Back in Bremen, the widowed Rumpff - who had long been aware of the strange deaths surrounding Gesche Gottfried - finally grew suspicious when he discovered a "whitish granular substance" in his salad and later on a ham. Though Gesche downplayed the discovery, after warnings from a neighbor, Rumpff had the substance analyzed by his physician Dr. Luce, who was horrified to confirm a high arsenic concentration. He had previously treated some of Gesche Gottfried’s victims without ever suspecting foul play.

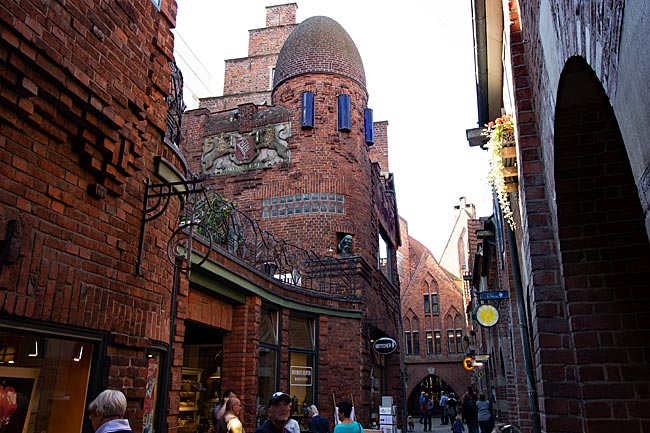

Following this revelation, she was arrested on March 6, 1828 - her 43rd birthday - and after several days in a cell at the Stadthaus, transferred to the newly completed detention house at Ostertor. She spent three years there until her execution by sword on Domshof. Despite numerous interrogations by Senators Droste and Noltenius, as well as conversations with Droste (with whom she nearly formed a friendship), no satisfactory answer was found for the motive behind her unprecedented murder spree of 15 victims.

Thus, this question remained unanswered when she was taken to Domshof on April 21, 1831, around 8 a.m., to be executed by sword. Emaciated and aged, she appeared before the silent crowd that had gathered for what would be Bremen’s last public execution. The verdict was read aloud once more; Senator Droste broke a wooden staff as a sign of the judgment’s finality, and Gesche Gottfried shook each judge’s hand after sipping from her final glass of red wine. Then she was strapped to the chair, and the executioner severed her head with a single sword stroke.

Spuckstein (Spitting Stone)

After taking casts of her severed head (from which death masks were later made - one copy is displayed in the Focke Museum’s Schaumagazin), it was preserved in spirits and exhibited at the museum on Domshof, with proceeds benefiting an orphanage. However, it has been missing since 1913. Her unburied skeleton was later destroyed during World War II. To this day, a so-called Spuckstein (a granite paving stone with a carved cross) can be found at the execution site between the cathedral and Neptune Fountain. In a gesture of disgust, passersby would spit on it.

A newspaper article published after her execution may explain why it took fifteen lives to uncover Gesche Gottfried’s crimes and bring about her arrest. The author describes how he searched in vain for any malice, cunning, or bloodlust in the expression of her severed head - finding instead quite the opposite.

Focke-Museum

Every city has its history, and in many cities, there is a museum that tells this story. In the Hanseatic city, it is the Focke Museum in the Riensberg district, where urban history is presented most vividly. The "Bremer State Museum of Art and Cultural History" was established in 1924 by merging two collections: the Gewerbemuseum, founded in 1884, and the Historisches Museum für bremische Altertümer (Historical Museum for Bremen Antiquities), founded six years later. The museum's founder, who passed away in 1922, also gave it his name.

read more ...

Domshof

In the shadow of the cathedral stretches the Domshof. Until 1803, the cathedral district - and thus the large square - belonged to the respective bishops, Sweden, and later the Electorate of Hanover, who ruled Bremen at times. The buildings, including townhouses, and the planting of numerous trees made the Domshof one of the most beautiful squares in the Hanseatic city during the 18th and 19th centuries.

read more ...

City Center: the main shopping streets

Another traditional café can be found at Sögestraße 42/44. The Knigge confectionery was established in 1889 and offers a variety of baked goods, chocolates, and ice cream, making it well-known throughout the city. Diagonally across from the café, branching off from the row of shops, is the glass-covered Katharinen-Passage, which - with an interruption - leads into the Domshof-Passage, ending at the Domshof. On this site, which now houses retail stores and a parking garage, once stood the namesake St. Katharine's Monastery.

read more ...

St. Peter's Cathedral

The history of the cathedral, Bremen's oldest church, begins with the Christianization of the region - originally settled by the Saxons - by Charlemagne in the 8th century. While it is uncertain exactly when the first cathedral was built on the highest point of the so-called Bremer Düne (Bremen Sandhill), it was likely destroyed by invading Vikings from Denmark in 858. The subsequent Romanesque structure, begun in 1041 and completed with its two towers in the 13th century, was later remodeled in the Gothic style during the 16th century.

read more

...

The Viertel

Even though the area around the two main streets and their many small side streets partially belongs to the Mitte district and partially to the Östliche Vorstadt, Bremen residents simply refer to it as "the Viertel." It is loved, hated, feared, and much more. In no other neighborhood of the Hanseatic city have contrasts been so openly - and sometimes violently - visible over decades as in the Viertel.

read more ...