![]()

![]() exploring Bremen & its surrounding areas

exploring Bremen & its surrounding areas

![]() You are here: worth seeing in Schwachhausen district

You are here: worth seeing in Schwachhausen district

Anti-Colonial Monument "Elephant"

Anti-Colonial Monument "Elephant"

If you leave Bremen's central station towards the exhibition halls and turn right at the end of the station forecourt, just a few meters away in a tree-lined green space flanked by several streets - the Nelson Mandela Park - you will encounter a symbolic piece of Africa in the Hanseatic city: the monument "Elephant." No other animal represents the fauna of southern Africa as impressively as these gray giants.

The elephant in Nelson Mandela Park stands on a pedestal containing a small room

But what does this have to do with Bremen? After the founding of the German Empire in 1870/71 (which actually extended over a longer period) and the proclamation of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV as German Emperor Wilhelm I, Germany rose to become a major power in Europe. Under the motto "A place in the sun," as later Chancellor von Bülow expressed it in the Reichstag in 1897, the Empire soon sought to participate in the division of the remaining alleged no-man's-land in the world. Not entirely conflict-free, after 1884 Germany grew under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck into the fourth-largest colonial power alongside other European states such as England, France, and Russia. Among the territories seized were large parts of Africa, including present-day Togo or Cameroon, German East Africa (today Tanzania and parts of neighboring countries), and German Southwest Africa (today Namibia).

Bismarck did not speak of colonies but of protectorates. The fact that primarily German trade and power interests - often against the original inhabitants of the regions - were protected there is shown by the genocide of the Ovaherero and Ovambanderu in German Southwest Africa in 1904. General Lothar von Trotha commanded the specially reinforced German Schutztruppe of around 15,000 men, which carried out a bloodbath among the indigenous peoples or exposed them to death in the waterless region of Omaheke. Up to 65,000 men, women, children, and livestock of the pastoralist tribes are said to have been killed this way; exact numbers do not exist, but the number of victims was very high. Later, the extermination campaign targeted the Nama and Damara, claiming another 10,000 victims. Many more people died in internment camps from malnutrition and forced labor. It was not until 2015 that a German government referred to this as genocide, though without acknowledging any obligations arising from it. Today, a memorial (OHAMAKARI) in the form of a circle of stones from the Waterberg region in front of the Anti-Colonial Monument "Elephant" commemorates this crime.

OHAMAKARI – Memorial for the Victims of Genocide in Namibia

It was the Bremen tobacco merchant Adolf Lüderitz who landed in 1883 in the small bay Angra Pequena in present-day Namibia, discovered and named by the Portuguese seafarer Bartolomeu Diaz in the 15th century, and "acquired" the surrounding land under fraudulent circumstances in 1884. Shortly thereafter, the area came under the "protection" of the German Empire. However, contrary to Lüderitz's expectations, the region proved not to be rich in resources, prompting him to sell his "acquisition" out of economic necessity just one year later to the German Colonial Society for Southwest Africa. The following year, he died, and the bay was renamed Lüderitz Bay in his honor. The name has remained at least unofficially to this day, as has the port city of Lüderitz, founded in 1883. Lüderitz was not only the first German to own land in present-day Namibia; he thereby created the nucleus of the colony of German Southwest Africa. Bremen had been a gateway to the world by sea since the Hanseatic period, and other Bremen merchants were also involved in the colonial goods trade, with the city's ports serving as points of arrival and departure.

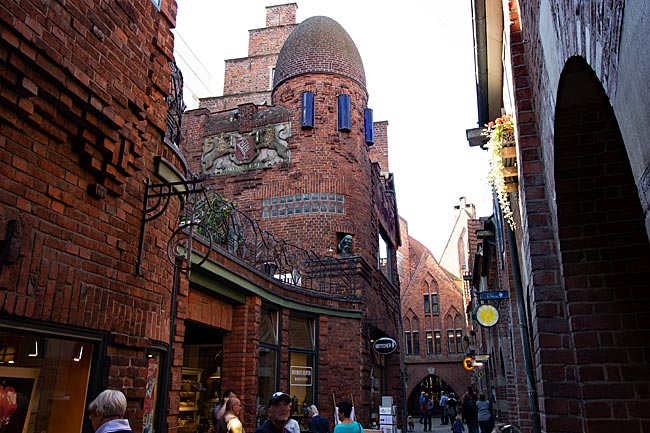

Germany lost not only the self-inflicted First World War but also all its colonies worldwide in 1919. Yet some viewed the surrender and the sometimes harsh conditions imposed by the victorious powers as a disgrace and the loss of the colonies as expropriation. One can understand the German Colonial Honor Monument, designed by Munich sculptor Fritz Behn - a African elephant - as an expression of this sentiment. The commissioning body for the brick structure was the German Colonial Society, which inaugurated the monument on July 6, 1932. However, even then, the construction was controversial in the traditionally more cosmopolitan Hanseatic city, as it stood not only to commemorate those who fell in the former German colonies during World War I but also for the oppression and exploitation of the indigenous population there. How quickly racist ideology and imperial fantasies - including those involving former colonies - gained traction among a significant portion of the German population from 1933 onward, leading to horror, terror, and death, is well known.

The African states have freed themselves, often at great cost in blood, from the yoke of colonial rule, yet many problems remain, rooted in that era of oppression. But Africa seems to be on a good path, also thanks to German aid.

Since its restoration and redesignation in 1989, the Elephant has stood as an anti-colonial monument for equality and justice and as a memorial against racism, oppression, and exploitation - a part of dark German history. The structure was almost reduced to a symbol of decay, however, as by 2016 the damage to its fabric had become so severe that action was required. Damaged stones and mortar joints were removed and renewed; the entire monument was thoroughly cleaned of vegetation and protected against future water ingress. The Moorbrand bricks used in construction had to be specially manufactured in an exact form, increasing the cost of the €180,000 restoration.

After months of work beginning in August of the previous year, the monument could be ceremoniously unveiled in February 2017 at what has been called Nelson Mandela Square since 2014.

Although a supplementary plaque on the street sign clarifies that the Bremen merchant Lüderitz was not a morally good person from today's perspective, it seems that this view was different during his lifetime and at the time of the naming

However, in the Hanseatic city, commemorations of victims of colonialism still stand opposite honors for people who made themselves infamous through their actions during that time - a fact pointed out by the "Decolonize Bremen" alliance. Although streets have been named after such individuals in the past, the path to successful renaming has so far proven difficult.

Cut.

Without diminishing or relativizing the described events and the associated responsibility, one must unfortunately acknowledge from a historical perspective that genocides - incidentally, a criminal offense under international law since 1948 - have left bloody traces on almost all continents over long epochs of known human history.

One such inhuman event is commemorated by a Khatchkar in a green space slightly apart from the Elephant. The inscription on a metal plaque explains that the Khatchkar "belongs to the oldest forms of Armenian art" dating back to the early Christian 4th century. These cultural artifacts are unique, as is this one, whose incorporated symbols represent life, fertility, continuity, humanity, and love, according to the text.

Since 2005, the Khatchkar has commemorated the genocide of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire that occurred 90 years earlier

Armenia borders modern-day Turkey, the successor state to the Ottoman Empire. With the slow but inevitable decline of the once-powerful Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, internal tensions between numerous ethnic groups also increased, with Christian Armenians being the primary victims. During massacres and persecutions in the two decades before World War I - particularly in the years 1894–1896 - between 80,000 and 300,000 of them were killed. But it was to get worse. In 1915, systematic annihilation began: massacres, death marches, prisoner-of-war camps, deportations. Between 300,000 and 1.5 million Armenians - women, children, men - lost their lives in the process. Worldwide, this systematic killing of civilians in the former Ottoman Empire is predominantly recognized as genocide. However, Turkey continues to vehemently deny these accusations, citing the state of war that prevailed at the time (World War I, 1914–1918) and the measures deemed necessary in its context.

Thus, not only these but millions of deaths from the two world wars, the Nazi killing machine, the Balkan War, or the wars "far away" - from a European perspective - in Indochina, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Ethiopia/Eritrea, Iraq, Sudan, or ... remain unpunished to this day: ignored, denied, ultimately even mocked as somehow responsible for their own fate (?). The warlike history of our species shows that the "never again" wish of the war-weary generations after the peace treaty recedes further and further into the background with the extinction of those generations and the subsequent ones who still experienced the consequences of war or had to listen to/hear the stories.

And the elephants? Despite protective measures, they continue to be slaughtered in large numbers by poachers solely for their tusks. Absurd!

Map

Further information

„Der Elefant!“ e.V.

Wachmannstrasse 39

28209 Bremen

Übersee-Museum (Overseas Museum)

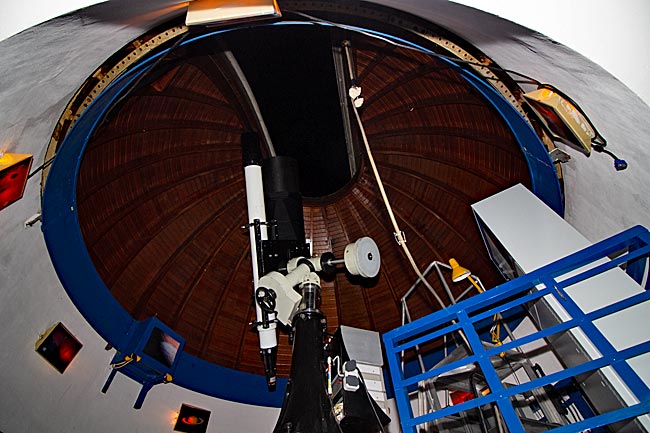

In 1896, the current Overseas Museum first opened its doors under the name "Municipal Museum of Natural History, Ethnology, and Commerce." The exhibits initially came from the "Municipal Collections of Natural History and Ethnography," which were partly displayed as a "Trade and Colonial Exhibition" at the "Northwest German Trade and Industry Exhibition" in 1890 with great success. Since its founding, the museum's concept has changed several times, evolving toward a stronger focus on museum education, which remains in place today.

read more ...

Bürgerpark (Citizens' Park)

A green oasis near the city center and a popular recreational area is the Bürgerpark. This extensive park, which adjoins today's Bürgerweide behind the train station, was initiated by the citizens themselves. In the early 19th century, the old defensive structures of the city had already been dismantled, transforming the ramparts into a landscaped park. However, as the city rapidly expanded throughout the century, demands for more green spaces grew louder and louder.

read more ...

Schwachhausen district

Built in 1913 at the central station, the Lloyd Railway Station served as a waiting area for emigrants who departed Europe from Bremerhaven aboard ships of the North German Lloyd. From here, their journey initially continued by train. After merging with the shipping company HAPAG, the company became HAPAG-Lloyd, headquartered in Hamburg. Directly across the street stands the anti-colonial monument "Elephant."

read more ...

Findorff district

The history of the Findorff district is closely tied to the moors of Lower Saxony's surrounding countryside. In 1819, the so-called "Torfkanal" (Peat Canal) was dug to transport peat as fuel, particularly from Teufelsmoor, by waterway to Bremen. Even today, the second peat harbor, built in 1873, exists in a smaller form within the district, with traditional peat barges still moored there. However, peat transportation no longer plays any role.

read more ...

Weser cruise from Bremen to Bremerhaven

Of course, you can take a car for a visit to Bremerhaven from Bremen or board the regional train at the main station. However, with suitable weather and enough time, it is more interesting to cover the route on the Weser by ship. The shipping company "Hal över" operates the connection from May to September. The ship departs from the Martinianleger near the city center along the Schlachte. Those who wish can even take their bicycle with them; additionally, you can pre-book a breakfast onboard.

read more ...